Ida B. Wells

By Esrom Habtamu

2024 Aug 13

Often, we are met with choices in life, and it is not easy to navigate this world without struggle. Nowadays, life has become more comfortable for most, but imagine being born in 1862 as a Black woman during an era marked by severe racism, segregation, and restrictions on voting—not only for Black women but for all women. The thought of living in such a time fills me with fear. I can hardly imagine what life was like and how you would need to constantly look over your shoulder as a Black woman in America during the 1800s and early 1900s.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born on July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi. She was born into slavery during the Civil War. Ida had no memory of her time in bondage, as she was only three years old when the war ended, and they were freed. However, she heard all about the horrors her parents endured—how her mother was separated from her siblings when they were sold, and how much it broke her heart. She saw the scars on their backs from the severe beatings they had suffered. Although Ida didn’t experience it herself, she felt the pain deep in her heart.

Ida was the oldest of eight children. After gaining their freedom, her parents, James and Elizabeth Wells, were very active in the Republican Party during the Reconstruction era. They learned to read and instilled in her the importance of education from an early age. Her father was a self-sufficient and independent man, trained as a carpenter, who managed to support his family without becoming a sharecropper—a situation no different from slavery. He was determined and refused to bow to pressure from his former enslavers when they told him to vote for the Democrats in 1867 when Black men were first allowed to vote. He also rejected their invitation to visit them, standing firm in his independence.

Surrounded by such strong parents, Ida later enrolled in Rust College, which had been founded by missionaries with whom her parents were associated. However, she was expelled after a dispute with the university president. Shortly after, a yellow fever epidemic swept through Holly Springs in 1878, and both of her parents, along with her infant sibling, succumbed to the disease. As the oldest of the seven surviving siblings, Ida felt a profound responsibility to provide for her family. Though relatives offered to take in the children, Ida refused to let them be separated as her mother had been from her siblings. She famously picked up a shotgun and declared, "I can take care of us." With that, the family stayed together, and Ida took on the responsibility of caring for her siblings.

Despite her young age and limited experience, she found work as a teacher to support her family financially. Ida spent her weekends washing clothes, preparing food, and organizing everything so her siblings wouldn’t struggle while she was away during the week teaching. Although her salary was meager, she did her best to make ends meet.

An aunt who lived in Memphis, Tennessee, learned of their situation and invited them to live with her. Ida agreed, and the family moved to Memphis. At the time, Memphis was a vibrant city with better opportunities for work and life seemed more hopeful. Ida found a job as a teacher in a small town outside of Memphis, a short train ride away. Ida loved the city and also the fashion. She would spend half of her earnings on buying cloth which I believe any young girl would relate to.Though she had to commute, she was content. In addition to teaching, she began writing articles for Black newspapers under the pen name "Iola," addressing issues of inequality and injustice faced by African Americans.

In 1884, while traveling on a train, Ida was forcibly removed from her seat despite having purchased a first-class ticket. Angered and hurt, she filed a lawsuit against the Chesapeake, Ohio & Southwestern Railroad Company and won the case at the local level. However, the decision was overturned by the Tennessee Supreme Court in 1887. This experience ignited her resolve to fight against injustice.

On March 9, 1892, three of Ida's friends—Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart—were lynched in Memphis. The men had been jailed and then murdered by a mob for defending their grocery store against white competitors. Thomas Moss, who was like a brother to Ida, was particularly close to her; she was the godmother to his daughter, and his death deeply affected her. Until this point, Ida had believed that lynchings were a response to actual crimes, albeit without due process. However, after this incident, she realized the true nature of white mob violence and began to investigate lynchings in-depth, launching her anti-lynching crusade.

Ida wrote a series of articles for the Free Speech and Headlight challenging the widespread justifications for lynching, which often falsely accused Black men of raping white women. Her most notable work, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, exposed specific cases of lynching and debunked the myths that underpinned this violence. She provided compelling evidence of the economic and social motives behind these brutal acts.

Southern Horrors reached a wide audience and was met with overwhelming support and admiration from the African American community. Her courage, determination, meticulous research, and fearless reporting inspired others to fight against lynching and to consider migrating north to escape the violence. However, the white community reacted with hostility. Ida received death threats, and her newspaper office in Memphis was destroyed by a mob, forcing her to flee the South.

Despite these threats, Ida was undeterred. Southern Horrors was distributed widely across the United States, and she continued to publish and circulate her work through Black-owned newspapers and organizations, ensuring it reached a broad audience. Her activism gained international attention, and she toured England and Scotland in 1893 and 1894, speaking about the horrors of lynching and garnering support from British reformers and journalists.

Ida's journey was just beginning. In 1895, she wrote a follow-up pamphlet, The Red Record, which provided a comprehensive analysis of lynching statistics from 1892 to 1894. The pamphlet debunked the myths that justified lynching and highlighted the systemic nature of racial violence. The Red Record further solidified Ida's reputation as a leading anti-lynching activist and provided critical information that fueled the growing movement against racial violence.

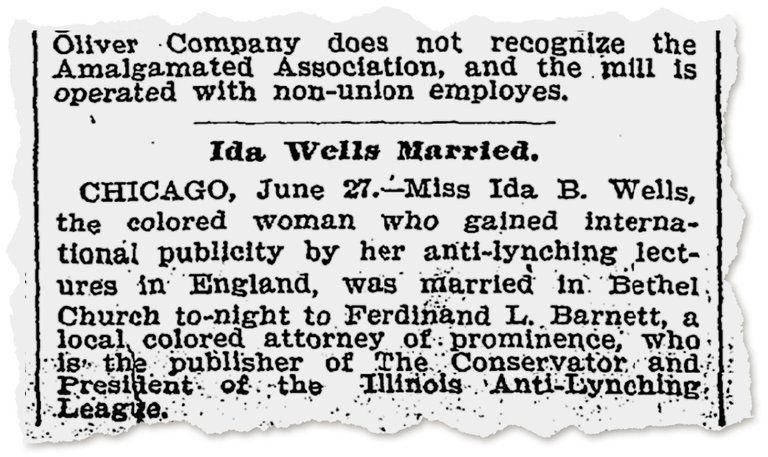

In need of legal support, Ida met Ferdinand L. Barnett, an attorney and the owner of Chicago's first Black-owned newspaper, The Conservator. Barnett, who was 10 years her senior and a widower, admired Ida's work and shared her passion for justice. They married in 1895, and their union was celebrated in Black newspapers across the nation, even drawing mention in The New York Times despite their previous distaste of her writing. The couple became a political power duo, and they had four children. Despite her commitment to her family, Ida continued her activism, traveling the world to advance her cause, often with her husband's support.

In 1909, in response to the Springfield race riots of 1908, where violent attacks against African Americans underscored the need for a national organization to combat racial injustice, Ida was invited to help found the NAACP. Although she was a well-known figure in anti-lynching activism, investigative journalism, and civil rights advocacy, Ida often found herself at odds with some of the NAACP's leadership. The tension arose partly due to strategic differences and partly from the gender and racial dynamics within the organization. Ida was known for her uncompromising stance and direct approach, while some leaders preferred more diplomatic methods. She also faced challenges related to her identity as both a Black woman and a staunch advocate in a male-dominated organization.

True to her nature, Ida eventually distanced herself from the NAACP and continued to work on issues close to her heart. On January 30, 1913, she founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, alongside her white colleagues Belle Squire and Virginia Brooks. The club aimed to educate Black women about their voting rights, encourage political participation, and mobilize them to vote. The organization sought to create a space that supported and encouraged African American women, as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) had largely ignored their concerns. The club played a significant role in electing Chicago's first Black alderman.

In the spring of 1913, Ida traveled to Washington, D.C., to participate in the National Women's Suffrage Parade. Despite being asked to march at the back of the parade with other Black women, Ida refused. Instead, she boldly joined the Illinois delegation, marching alongside white women, making the march an integrated one.

Ida B. Wells was an incredible woman who fought for justice with all her might. She cared deeply about people and sought justice for those who were marginalized. Not only did she do remarkable work in journalism and investigations, but she also supported the community by helping Black men who had migrated north and were struggling. She encouraged and guided them when the rest of the world had given up on them. Ida B. Wells died on March 25, 1932, due to kidney disease.

When I think of Ida B. Wells, I see a heart radiating with love and strength. Her decision to care for her family after the loss of her parents reflects the deep sense of responsibility she carried. In her, I see the legacy of her parents—the price they paid for their freedom lived on through her actions. At just 16, I imagine her managing household chores and caring for her siblings before heading to work each week. Ida B. Wells epitomizes bravery. In the face of danger, when most would flee, she chose to stand and speak out, even at the risk of her life. Her activism was deeply inspired by her love for people; she always fought for others when she could have led a more comfortable life. I believe that delving into her life story can inspire us all to be strong, and dedicated, and to see beyond ourselves in our daily lives. Perhaps.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get weekly updates on the latest stories.